Thoughts About My High School's Math Curriculum

Published: 2/4/2019

I went to high school to Thomas Jefferson High School in Pittsburgh, PA (not the famous one in Alexandria, VA). I wrote an email to my math teachers there talking about my thoughts about our high school math curriculum now that I’ve been through an undergrad, currently taking grad courses, and have a full-time job doing math for a living. I’m pasting the emails as-is here, with some additional formatting. Please let me know if you have any comments or criticisms.

Hey,

In my job as an artificial intelligence researcher, I am exposed to and use math every day. Usually this takes the form of probability and mathematical statistics, calculus 2 stuff and calc 3 partial derivatives and double integrals, linear algebra, and then some conglomerate stuff like vector calculus, calculus of variations (rarely), and differential equations (rarely).

I took a whole bunch of math in my undergrad, and now I’m taking some grad level math courses at CMU. Even with those courses, I had to self-teach myself the majority of the math I now use daily, which meant I had to fall back on my existent knowledge. I realized today that there were things I wished I learned in high school, or at least got an intuition or appreciation for, that would help me today.

-

Proofs. In high school, I was only ever introduced to two-column proofs, which no one ever uses in real life (unless they’re doing computational proofs). The most useful proofs I have seen, and struggle with the intuition at times, are induction and contradiction. If the principles of these proofs could be introduced in an intuitive way in high school, I bet kids would be much more capable of taking small concepts and generalizing them to large lemmas.

-

Math notation. As you know, everyone and their mother just makes notation up and uses it however they want, as long as they’re consistent within their textbook, research papers, etc. It took me forever, and this is something I still struggle with, to learn to read math. It’s like its own language. I think it’s something a lot of people struggle with. This handout (http://pi.math.cornell.edu/~hubbard/readingmath.pdf) helped me create a path towards understanding how to parse these arbitrary symbols in a reasonable manner. I would have loved to see this during high school.

-

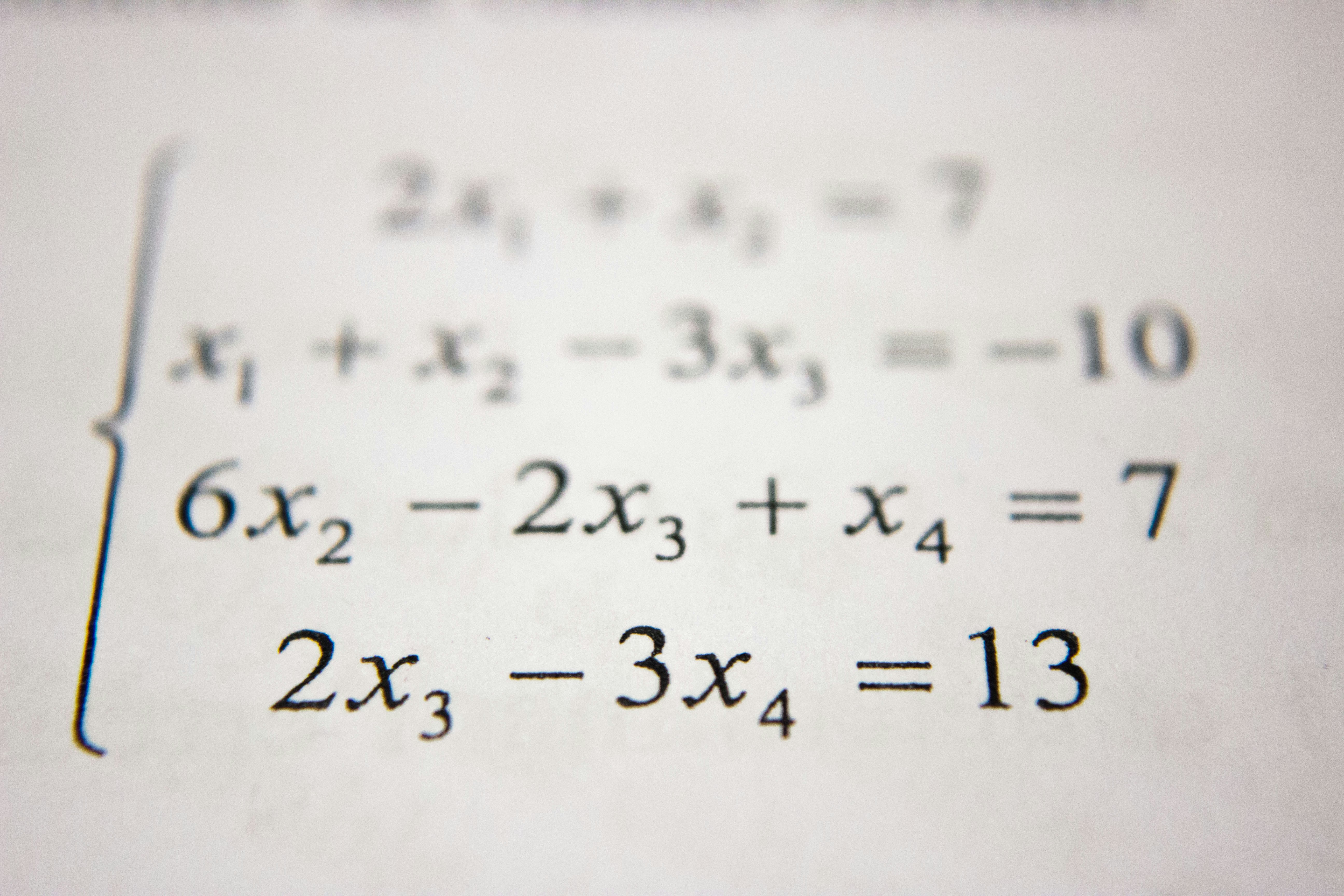

“Tricks”. Every time we’re proving something or deriving something, little math hacks always show up. Re-arranging equations to help with elimination, multiplying by inverses which have the effect of multiplying by 1, but again, help with elimination of variables, and more. These tricks, unless I’ve seen them before, completely stump me. I have no idea when I’m staring at a piece of paper for the first time where and how I should use a trick. Learning to identify these patterns earlier in my mathematical life would’ve been a game changer. I know this is a difficult one, because it’s not something you can just teach. But just exposing students to “this is a thing that you’ll see every day in math, and the textbooks will just gloss over it,” would be amazing.

-

Converting word problems to math. This is a fundamental skill we work on since elementary school, but for some reason I found certain things in high school suddenly stopped doing this. Sometimes when I’m given a real-world problem, like “Estimate the average number of people leaving an area given that a storm of a certain intensity is approaching,” I find myself struggling to turn that into actual math. After a while I’ll eventually realize that this is just conditional expectation, but then choosing the correct random variable to define certain parts of the problem, etc., is difficult. Obviously kids aren’t doing all this stuff at TJ (yet, I know probability is a course to be offered soon), but the general point is that this is an important skill. You guys already do a good job of it, but I would have loved to see more of it versus rote usage of formulas (like on the AP test).

-

Inequalities. I know in pre-calc we have a whole section on inequalities, but I guess I mean more advanced usages of them. Let me start with an example. When we’re working with dependent joint distributions, calculating the probability of some pair results in a double integral where the bounds are in terms of and themselves. Therefore, the support of the joint distribution is also defined in terms of and , usually in the form of an inequality. Converting the integral bounds to what the support should be, and vice versa, is non-obvious to my mind, since the only time I exhaustively did inequalities was in high school. This may be a failing of my undergrad education, but it may be an opportunity for high school to succeed. Obviously my example is highly contrived and way too advanced for high school, but I can imagine simpler examples where inequalities like would come up, and a high schooler should be able to reason about those.

-

Sums, their notations, and their uses. I’m pretty sure we learned about arithmetic and geometric sums in pre-calc, but they’re used so often in math that they should be a bigger deal. People are still so scared of the “big E” () and the “big pi” () after leaving high school that I think we’re doing a disservice by not introducing the intuition behind sums and their notation a little bit better. As far as I remember, we talked about arithmetic sums, did a toy example, then jumped into the sum identities (like factoring out constants, etc.). Most people will probably use sums in their careers, and I think some extra intuition and exposure will go a long way with making people comfortable with sums.

Not all of these thoughts are valid, or actionable. They’re just things I wished I knew more about in high school, because I think having these tools would’ve made the rest of my math education that much easier. You both are the sole reason why I love math, and you both do a fantastic job already. I hope that any of this feedback is helpful. Let me know if I can clarify, I’m just rambling at 2:30 in the morning.

Also, what the heck is a lemma, claim, theorem, proof, axiom, etc., anyways? I didn’t know that in high school. All of these terms showed up in textbooks when Matt Brock and I tried to teach ourselves Calc 2 for the AP Calc BC exam.

Setting up people to succeed when self-studying, in my opinion, is the only way to make successful TJ mathematicians. If you can’t read a textbook, you’re stuck being dependent on a teacher, which means when college hits, you’re screwed. How can we set up students to self-study effectively?

Thanks for everything and setting me up for success.

Ritwik